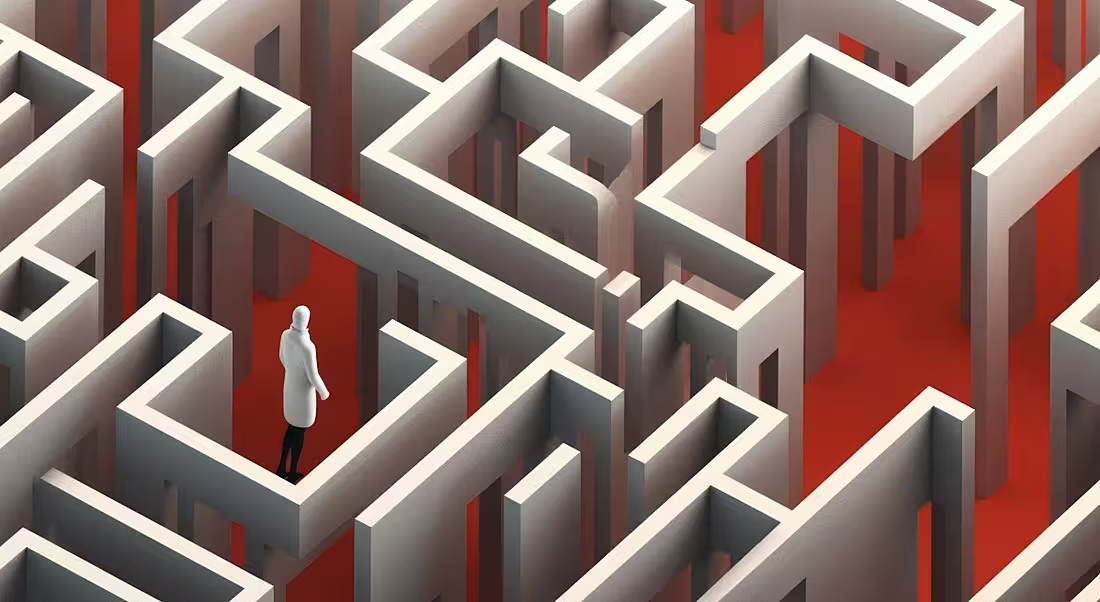

Scientist Tammy Strickland says there needs to be a cultural reckoning in academic circles before things get better for postgrad workers in Ireland.

“There are just so many areas that are problematic,” says Tammy Strickland, a researcher with the Royal College of Surgeons (RCSI) in Dublin and member of the Postgraduate Workers Organisation (PWO), a union that is agitating for reforms in the way postgraduate workers are treated in Ireland.

Before we get into issues such as poor work-life balance, Strickland gives an insight into the financial situation she and others like her face. “I’m very lucky to live with my partner because before I decided to do that I couldn’t rent anywhere,” she says, adding that the stipend researchers get paid means landlords don’t want to take a chance on them as tenants. “Essentially everyone is living on a kind of minimum wage.”

‘No one should have to go through this to break into a field. We’re not making it accessible’

– TAMMY STRICKLAND

Researchers are expected to do a lot of unpaid labour, such as teaching, which Strickland says “comes with the territory”. It’s just expected. “Ultimately, the unions have existed for a long time and nothing has changed in about 10 to 15 years with respect to wages. Now, because of the cost of living, everyone wants to do something about improving workers’ rights.”

“I suppose what PWO has been trying to do is to organise protests. We’re modelling ourselves off what happened in the UK, we want ideally to be more like Scandinavia in terms of workers’ rights, but there are a lot of steps to get there.” The group wants members to be recognised as workers with appropriate social protection.

“I would say the UK have a similar process to us. Last year there were protests and then there was a strike and then workers’ conditions were improved. And it was publicised a lot. I think we’re trying to do a similar thing,” Strickland says. But she doesn’t hold out much hope for change.

Lack of empathy from higher-ups means issues persist

The problems are symptomatic of a wider cultural rot in academic hierarchies, she says. “There is an attitude in the culture that people higher up say, ‘We went through that as well.’ It’s not everyone, some people are supportive of change, to be fair, but a lot don’t really pay much attention to the problems and the desperation.”

“There’s a bit of a lack of empathy because the attitude is often, ‘Everyone struggles in order to get into the field’ – which is just terrible because no one should have to go through that to break into a field. We’re not making it accessible.”

If the so-called initiation into a career in academia is poverty and stress, Strickland says it is absurd to expect early-career researchers to contribute to innovation. And yet they are expected to, and given not a lot of credit for their work until they achieve success through publications, projects or research breakthroughs.

“There is no incentive other than what they call passion or getting results for the lab,” says Strickland. “There’s no financial incentive for that, and for me, that is a little exploitative too, because you don’t get paid per hour. So, ultimately, you’re doing something for the long-run benefit. But in the short term, you’re harming your health and your wellbeing.”

She thinks that a lot of individual universities’ programmes on work-life balance for researchers are there merely to pay lip service. “I think sometimes, even the most well-intentioned people in academia can say things, but their practice is a lot different. Making sure that people are protected is very different from just saying the right words in front of other people,” says Strickland, adding that “ultimately the system is still like this”.

Frustration at the lack of change

“I’m frustrated with people saying things and not actually implementing anything properly. For a long time, it was looked on as a university-to-university issue but it’s more than that.” She acknowledges that however difficult it is for her, others have it even tougher.

International students, parents and those renting alone are particularly up against it. The lack of care and support, Strickland says, comes from a lot of people in senior academic positions who create a gated academic community which is actively shutting out people who do not conform to a narrow ideal of what an academic looks like.

“You will lose so many people who might have good ideas,” she warns. “It does stifle innovation because the diversity of who could contribute to ideas is lost. Because it is classist, ableist and sexist … all of the ‘ists’, unfortunately, are brought into play and it’s really hard and people quit. And I don’t blame them because it’s very, very tough.”

‘There is a very real issue in relation to the level of stipends paid to students in Ireland, not least due to the increased cost of living and to ensure equity for all researchers’

– DR RUTH FREEMAN

“If there’s no worker protection, there’s no incentive to go into academia in the first place,” Strickland says ,returning to what the PWO has been saying. “I think we lose out on a lot of talent by it being such a hard place to be in financially. It can be completely impossible to even enter. I know it was a huge decision for me to go in again … It’s prohibitive.”

So, what are her hopes? If she has any? “I think what would be nice is to get more people to speak and speak freely and feel okay to speak about their experiences.” She mentions the WhatsApp group she has with other Irish-based PWO members. “Some of the things that people type in … it’s just heart-breaking, especially the international students. It’s just heart-breaking what happens.”

What is being done, or not?

Science Foundation Ireland’s (SFI) director of science for society, Dr Ruth Freeman, responded to some of the grievances postgraduate workers have been airing. “Through competitively funded awards, SFI currently supports around 2,200 PhD students; the majority of whom will go onto careers in industry,” Freeman said.

“There is a very real issue in relation to the level of stipends paid to students in Ireland, not least due to the increased cost of living and to ensure equity for all researchers,” she acknowledged, adding that SFI welcomes the recent review of postgraduate working conditions in Ireland by the Government. She said SFI will work with the Department of Further and Higher Education, Research, Innovation and Science (DFHERIS) “to review the state supports for PhD students” and “implement any proposed changes”.

‘I’m frustrated with people saying things and not actually implementing anything properly’

– TAMMY STRICKLAND

Freeman said there are lots of programmes that support postgraduate researchers “which can help them to progress their career towards industry, academic research or the public sector.” These include challenge funding schemes, early-career fellowships and opportunities for researchers to work on transferable skills and industry partnerships.

When asked for comment on the negative reaction from many in the postgraduate community to its report into working conditions, a spokesperson for DFHERIS reiterated that the report did recommend an “increased stipend level, with an optimum target of €25,000”.

However, the spokesperson added that due to potential impacts of such an increase on public finances, “significant additional work will be needed in order to give effect to such a recommendation” – meaning workers will have to wait.

10 things you need to know direct to your inbox every weekday. Sign up for the Daily Brief, Silicon Republic’s digest of essential sci-tech news.