Ireland has the potential to create 20,000 extra jobs in the manufacturing sector within six months – that’s according to the Minister for Jobs, Enterprise and Innovation Richard Bruton, TD. Bruton is on to something here. In the tech world, while some say ‘software is eating the world’ (and it is), people still get excited by shiny physical objects.

Bruton has established a Manufacturing Development Forum tasked with driving the development of Ireland’s manufacturing sector, which employs some 230,000 people today.

As well as assembling a group of manufacturing industry experts across the food, engineering, health/life and technology sectors, the forum will tie in with other developments, like the Potential Exporters Division at Enterprise Ireland, a new Development Capital Scheme for mid-sized high-growth companies and extending corporate tax exemptions to businesses targeting exports to high-growth markets.

“Central to the Government’s plan for jobs and growth is our determination to create a powerful engine of manufacturing industry,” Bruton said.

“We have a strong base of high-end, world-leading multinational manufacturing companies operating in a range of sectors – we must aspire to replicate the success of international examples like the mittelstand companies in Germany, by developing this level of success in the indigenous economy also.”

This strategy is timely. In the mid-2000s, a dangerous and irresponsible idea began to float in Ireland that it no longer needs manufacturing industries. Remember this was at a time of economic largesse and the irresponsible inflation of a property bubble that wrecked businesses and lives. You can’t export houses and thankfully many of those so-called ‘thought leaders’ have been consigned to the dustbin of history.

Why Ireland needs manufacturing

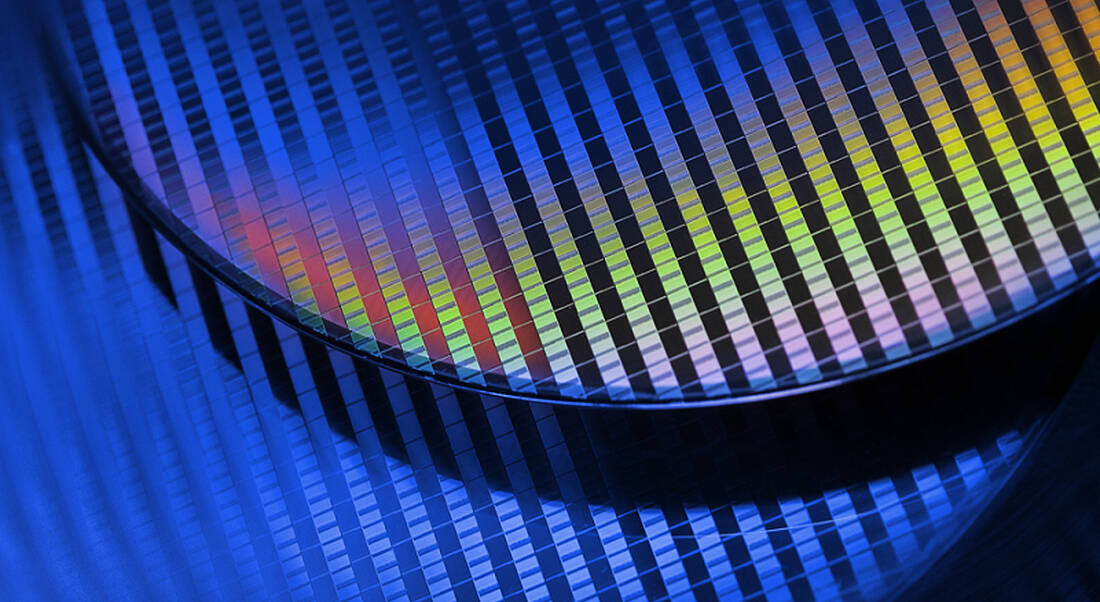

Without a manufacturing or engineering core, no economy can claim to be a tech industry leader. This is a lesson Silicon Valley is just now coming to terms with. Silicon Valley’s name comes from the particles of sand that make the chips that power computers and phones we carry today.

Whenever Apple reveals new hardware like the MacBook Air or there is talk of a mini iPad or new iPhone, this fires more imagination in consumers’ minds than what Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg had for breakfast that day. Yet look at the back of any piece of Apple hardware and you’ll see the words ‘Designed by Apple in California Assembled in China’ etched on the back. I sometimes imagine those words may as well be etched painfully on the hearts of the thousands of engineers and inventors that built Silicon Valley into what it is today.

That mindset, I believe, is returning. Asia will remain the epicentre of technology goods production but there is an opportunity to play a fundamental role in product design and development and orchestrate a global supply chain.

Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey’s next big thing is Square, a piece of hardware that latches onto smartphones to take credit card payments.

Microsoft is tentatively going after Apple’s integrated model with its own piece of hardware for personal computing, the Surface.

It is only a matter of time before Facebook flexes its muscles to produce its own mobile OS and hardware devices.

Irishman Liam Casey has become something of a kingmaker in Silicon Valley and Asia; his company PCH International manages the design, product development and ultimate delivery to the shop shelves of major consumer electronics goods with household brand names. In recent weeks, PCH, which employs 80 people in Cork, revealed plans to employ an extra 1,500 people at a facility in Shenzhen near Hong Kong in a move that will grow employment to 3,000 worldwide.

Just prior to that, Casey’s company acquired a Silicon Valley product development company called Lime Lab, led by top product developers Kurt Dammerman and Andre Yousefi, giving PCH a powerful edge within the tech world’s spiritual home where finally hardware is hot again.

Why hardware matters

I got my grounding in technology not by visiting trendy-but-dull conferences full of ‘how I made it’ types with pimples still on their chins, but by hoofing my way through manufacturing facilities ranging from Apple in Cork, where they were still slamming chips onto printed circuit boards, SCI in Fermoy, EMC in Ovens, and HP in Leixlip, where inkjet cartridges were being filled and programmed.

Arguably the growth of the tech industry in Ireland owes itself to the massive growth of the PC industry almost 20 years ago and the nature of the operations that have remained have changed dramatically to include data centres and the creation of intellectual property. Ireland produced the lion’s share of Intel Pentium processors for the world in the 1990s, thus playing a key role in the history of the computer industry.

Most of those tech giants that have remained have moved up the value chain to higher-level supply chain mixed with R&D work while much of the lower value work has shifted to Asia.

But in Intel’s case it is gearing up for the next iteration of computer chip manufacturing in Ireland, generating an additional 1,000 jobs in the process proving that Ireland has what it takes to shape the future dynamic of computing at a high level.

That’s why I think the IDA’s policy in recent years of assembling R&D investments close to manufacturing has been a genius approach. Excelling in manufacturing is not about taking on low-value work like PCB assembly in the 1990s, it is about moving to the next big (or small) thing.

Take nanotechnology, for example. Nanotechnology, the science of ultra micro electronics and pharmaceuticals, has the potential to be a major engine of growth in the Irish economy and exports could be doubled from €15bn today to €30bn by 2015.

Skills will be the ultimate arbiter

But there is a tragedy that has unfolded and it was one of the last things that Apple’s Steve Jobs said to US President Barack Obama in the year before he passed away last October. Jobs pointed out that at a time of high unemployment in the US, some 300,000 jobs that went to Asia could have been created in the US had the right education policies and skills existed.

It is in schools where this change has to begin, where collaborative teamwork and engineering, linguistic, entrepreneurial and management skills should be fostered.

America never got over the loss of its display technology industry to Asia, for example. That industry was simply allowed to slide away and today it happens to be the hottest area of technology.

But Jobs’ point to Obama was not about clawing it back, it was about developing the engineering skills and capabilities that are core to capturing future waves of innovation and managing it.

Ireland has not been immune from this change. As Bruton pointed out this morning, employment in manufacturing has declined from levels of 299,600 in 1997 to 239,700 today. Its contribution toward total employment has fallen from 22pc in 1997 to 13pc today.

But Bruton points out there is still considerable potential for the manufacturing sector in Ireland.

I’ve spoken to PCH’s Liam Casey at least four times in the past year. Casey, who has been named Ireland’s start-up ambassador to Asia by Enterprise Ireland, points out each and every time that you don’t have to assemble everything at home, but you can manage it, design it and ultimately produce it.

Manufacturing has a future in Ireland but it is a high-level future where we need the skilled engineers, designers and supply chain specialists who can orchestrate a world of change and ideas.

The new Manufacturing Development Forum has its work cut out for it. But my advice is see what change you can start in the schools and colleges from an engineering skills perspective – and to catch the future waves in the long, prosperous future that the technology industry promises should we decide to hold onto it.

Computer wafer image via Shutterstock