Image: © Tada Images/Stock.adobe.com

University of Strathclyde’s James Bowden and Bangor University’s Edward Thomas Jones talk possible lasting effects of the GameStop hedge fund events driven by online communities and media.

A version of this article was originally published by The Conversation (CC BY-ND 4.0)

In the dying days of 2009, Rage Against the Machine achieved the unlikeliest of Christmas number ones with a re-release of their anti-establishment anthem, Killing in the Name. This was driven by an online campaign to give a great festive bloody nose to Simon Cowell, whose latest X-Factor winner was denied their routine annual spot at the top of the charts.

That protest against a creatively bankrupt mainstream pop media became a case study in the power of an online crowd with a strong narrative. It finds echoes today in a very different arena: the current attack on Wall Street hedge funds by retail traders via the Reddit forum r/WallStreetBets.

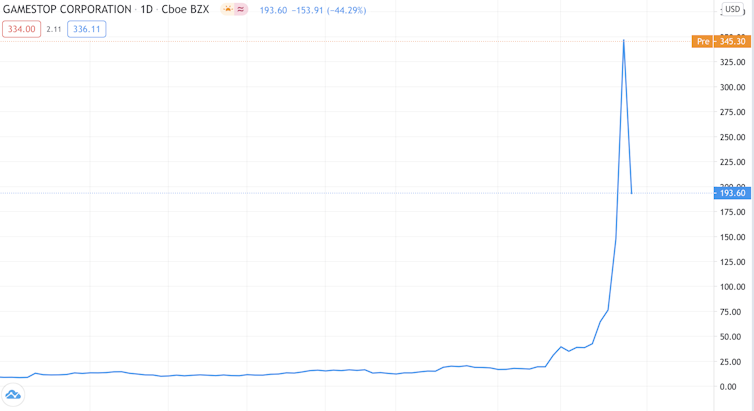

When exchanges opened in the new year, shares in GameStop, a Texas-based chain of computer games stores, were swapping hands at $19 each. By the end of Tuesday 26 January, they were worth $347 – an increase of more than 1,700pc.

GameStop price action. Image: TradingView

Driven by a David versus Goliath narrative of revenge against previously untouchable Wall Street “fat cats”, as one of the forum’s moderators called them, the surge was coordinated by the almost 5m members of WallStreetBets, using apps such as Robinhood that allow anyone to trade financial securities and derivatives for little or zero commission fees. In the words of one of these traders: “People are risking their lives to wage war against the suits and it brings tears to my eyes to watch them do it.”

Beaten at their own hedge fund game

This produced an estimated $6bn in stinging losses for hedge funds and activists “short selling” GameStop shares, according to Bloomberg. Short selling is a bet on stock prices going down, and is done by borrowing shares, selling them and then buying them back later to return to the lender – hopefully at a reduced price.

Critics argue that hedge funds that engage in short selling have an incentive to push down prices in questionable ways, such as spreading negative rumours about the company’s future. The practice was blamed to some extent for major financial institutions going into free-fall during the global financial crisis in 2008.

By buying GameStop to hurt those with short positions, retail investors employed a classic Wall Street tactic that hedge funds use against one another. Buying enough shares to cause the price to surge forces short-selling hedge funds to buy back the borrowed shares at a higher price to cover their positions, which in turn pushes the price higher. In Wall Street parlance, it’s the “short squeeze”.

Hedge funds such as Melvin Capital had to swallow soaring losses as the share price hit certain levels and triggered margin calls where they had to immediately repay their lenders. Melvin only survived thanks to a cash injection of $2.75bn from other hedge-fund backers.

In previous years, such an attack would have been quickly swept aside by the larger firepower of hedge funds and established Wall Street institutions. Activist short sellers also kept the lid on things by publishing damning research on targeted firms. Our study from 2017 demonstrated that a short-seller thesis can almost instantaneously affect online message board sentiment and send investors fleeing.

The difference now is that retail investors have much better access to the financial markets, swelling their numbers and their ability to collectively move prices. The number of users on Robinhood has increased from 500,000 in 2014 to 13m in 2020, and trading stocks is the most common use for the US government pandemic stimulus cheques in almost every age bracket.

The empire strikes back

Robinhood and other trading platforms banned trading in GameStop shares around the time they peaked, sparking outrage at a perceived rigged game tilted towards the big players. Both Democratic and Republican senators have condemned this decision to block retail investors while hedge funds can continue to trade.

The platforms claim they had to impose temporary suspensions to protect their own financial positions from the risk of targeted stocks tumbling and retail traders who have borrowed to maximise their buying power suddenly racking up losses they can’t afford to cover.

The debate over how regulators should respond to this conflict is meanwhile intensifying, raising the prospect of new rules that discriminate against retail investors. That could fatally undermine trust in the regulators, since they would effectively be saying it’s alright for Wall Street to employ short squeezes, but not the little guys.

Either way, these events have brought issues to the fore that regulators would have needed to address further down the road anyway, since the trading game has clearly changed in the last couple of years. For example, one new danger is an unfriendly foreign country feeding fake news into social media to enrage retail investors about perceived unfairnesses, which galvanises them into attacks that prevent the markets from working efficiently.

After all, some would argue that short sellers are unfairly portrayed as villains in this David versus Goliath battle. They help to keep markets liquid by making share purchases easier for those who do want to buy a particular stock, and they can put a spotlight on companies that are poorly managed, dishonest or engaged in poor corporate governance.

As a New York Times profile of notorious short-seller Andrew Left states, “In a town with a dozing sheriff, vigilantes become the agents of order.” Left’s fund, Citron Capital, made a 100pc loss on its short position in GameStop.

So how should the regulators play this? They may not want to curb investor discussion in online communities, even if it were possible, or try and set parameters about what constitutes manipulation and honest discussion of a particular stock.

One option might be to increase their monitoring capacity, perhaps through some kind of early-warning system based on the volume of online chatter and the sentiment being expressed. They could feed this information to the trading platforms to let them take a view on temporarily limiting trading on those securities.

‘I won’t do what you tell me’

Nobody knows how the present situation will end. The intense activity by retail investors could prompt a wider sell-off by forcing hedge funds with short positions to sell other shares to raise the cash to cover their losses. This could hurt companies and investors that were only spectators in this battle, with potentially far-reaching consequences.

For those worried about the potential for chaos, Rage Against the Machine might offer a crumb of comfort. Since that Christmas number one, numerous attempts to achieve a similar feat have been less successful. The collective action was diluted by the sheer number of copycat campaigns.

Similarly, we have seen campaigns by traders launched against Blackberry and AMC Entertainment, and there are rumours of a similar strategy being employed against American Airlines. Whether they reach similar levels as GameStop remains to be seen.

Either way, the crowd will regroup and regulators will need to learn valuable lessons from this episode. Having shown what a crowd of renegade investors can achieve, this could well have opened up a powerful new front in anti Wall Street activism.![]()

![]()

By James Bowden and Edward Thomas Jones

James Bowden is a lecturer in financial technology at University of Strathclyde and Edward Thomas Jones is a lecturer in economics at Bangor University.