David Quin, animation lecturer at IADT, discusses his career path and why he’s hopeful about a brighter future for people in the industry.

Animation is thriving in Ireland. With studios such as Kavaleer Productions, Brown Bag Films and Pink Kong Studios, among many others, the country is home to plenty of talent. And just this week, South African animation studio Triggerfish announced Galway as the chosen location for its first international base.

To learn more about working in the field, I spoke to David Quin, who has been lecturer in animation at IADT (Ireland’s Institute of Art, Design and Technology) for 19 years. Quin is currently one of the co-chairs of the institute’s animation undergraduate programme and continues to work on his own creative projects.

‘Anyone can still dream up the next big thing – the next Peppa Pig, the next Grand Budapest Hotel’

– DAVID QUIN

What kind of career path does an animator typically take?

A career path in animation is very rarely straightforward! I’ve worked as an animator since the late 1970s, starting work in my father’s tiny animation business, making childrens’ programming for RTÉ. We started as stop-motion animators, shooting on 16mm film.

In the mid-1990s, I successfully switched over to CGI (computer animation), working for seven years as a freelancer for Brown Bag Films on adverts, corporate projects and short films. I’ve since switched back mostly to stop-motion animation and I’m now interested in de-digitisation and alternative modes of animation creation and delivery.

What are some important lessons you have learned in the industry?

Assume nothing. And persist. Follow your instincts and prepare for a long, long journey in animation. I tell my students, “Animation is a life sentence!” Animation is not one thing anymore – it’s a huge multidiscipline, with diverse opportunities for the most wide-ranging talents.

Most exciting of all, young people now are already evolving the animation practices of the future – new projects, new ways of doing things, new business and new creative models. We just haven’t heard of them yet!

Though animation is well over 100 years old, there’s still a ton of new and exciting work to be done in our multidiscipline. I believe animation’s best work is still ahead.

What have been your biggest challenges?

Conventionality and conservatism. Though we have good funding opportunities and supports in Ireland, through Screen Ireland especially, the global animation industry and the funding are dominated and controlled by risk-averse and highly unimaginative people.

So, the same big, safe companies tend to get funded. Exciting and innovative projects either die away or are forced to rely on self-funding and other scraps. In animation, self-funding will allow small projects, short films, to scrape onto the screen, but TV projects and cinema are more or less impossible to produce.

But, again, we must persist, believe in what we’re doing and keep trying to get there, despite all obstacles.

Is it a tough industry in terms of work-life balance?

Yes. This is something which must be improved over the next few years. The young people coming into the industry deserve to work in ethical, ecological and truly human enterprises, doing their best creatively and entitled to hold onto some ownership of the work they do.

There must be far more respect for diversity, families and health in the business. For too long, animation around the world has been dominated by a macho culture of all-nighters, crunch times, poor pay, zero IP ownership, high stress and poor mental health.

I blame much of this on the fact that most animation companies are still run by guys, some of them not very ethical people. This has to change and that necessity to change is also exciting.

As the animation working models improve, the animation work will improve too. Risks will be taken. New, good things will emerge, outstandingly inventive work will be done, and animators will live better lives.

What are the most important skills and attributes to succeed in the field?

I believe animators need to be able to get on with other people, to work with them and to allow everyone to work to the best of their ability. Most animation work is done in creative teams.

Confidence, self-belief and persistence are also essential. I also value imagination, imaginative agility and a sense of humour, but not all people working in animation are imaginative.

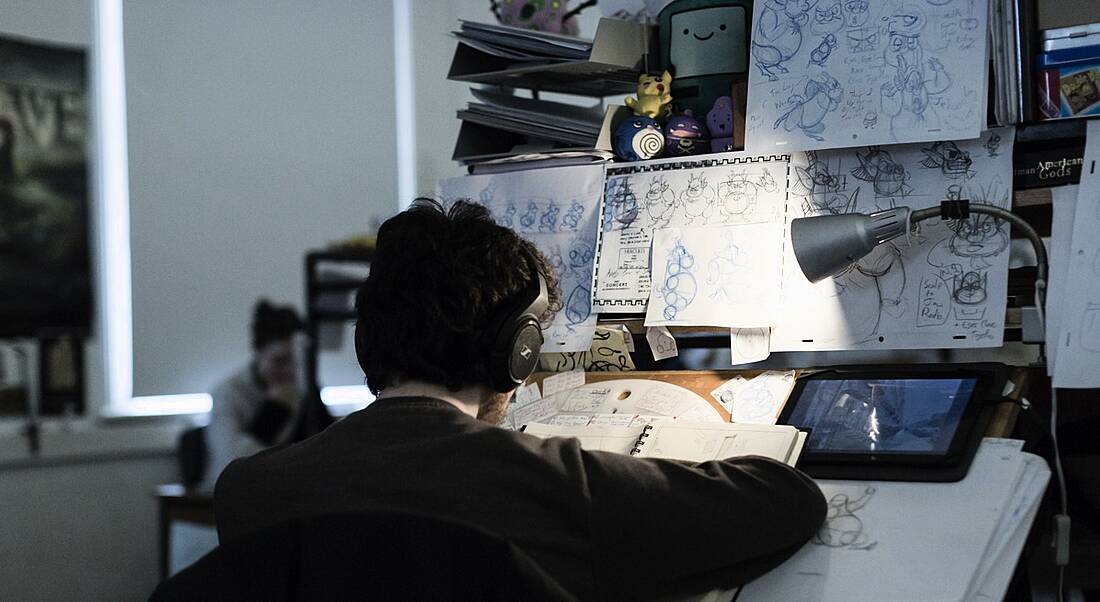

In terms of practical skills, a willingness or ability to draw makes things much easier and it’s best if you learn some strong digital skills somewhere. Drawing on paper is still the most effective and efficient way to evolve new visual ideas and to take imaginative visual risks.

Today, almost all animation must be translated into a digital delivery, so dexterity with computer hardware and software is more than useful. In animation, as in all film, you will get opportunities. Making the most of those opportunities is what matters. When an animation opportunity arises, you need to be able to use the right tools.

What does it take to get into an animation course?

On our undergraduate programme, we look for a willingness – maybe not yet an ability – to draw, and observational drawing, often notebooks of animals, people, hundreds of very quick sketches.

After that, we need to be convinced that applicants are really interested in animation, convinced that this is what they really want to do. Because it is a tough learning curve and it’s often challenging work.

What do undergraduate courses look like?

We’re rewriting our undergraduate programme at the moment. It’s currently a four-year programme, with each year of study divided up into discrete project-based modules. Years one and two concentrate on allowing people to develop skills and the ability to learn skills.

The final years allow students to find their own pathway into the multidiscipline, to specialise if they wish, but especially to make something completely new, something imaginative, something we’ve never seen before. We’re also encouraging and helping students to develop business and ethical skills and an international perspective.

Is animation a rewarding career, in your opinion?

Animation is rewarding because the possibilities are endless and because, as I’ve already said, the best work is still ahead of us. Anyone can still dream up the next big thing – the next Peppa Pig, the next Grand Budapest Hotel. That’s why I’m sometimes almost disappointed that our really talented graduates just get jobs in big studios, often doing pretty uncreative work on terribly mundane projects.

I’m confident that our graduates are so much better than that. I’m confident that our graduates can – and still will – set up new and exciting creative projects, new ways of doing business, new studios and the creative industries of the future. I’d be honoured to work with most of our graduates in the morning.

Do you have any advice for anyone considering a career in animation?

Draw! Keep creative notebooks – small notebooks you can jot down ideas and sketches. Try to learn every day. Try to work well with other people, especially with good, creative people.

Remember always that animation is a long haul – a marathon rather than a sprint. You need to develop confidence and persistence. It helps to be imaginative and agile.

Have self-respect and look after your physical and mental health. Don’t work for nothing. All creative artists deserve to be paid for their work and deserve to make a decent living as professionals. And have fun!